Police handling of hate crime: A pilot project to use VR technology for professional development in sensitizing police officers to the experiences of victims of bias crime in Hamburg

Prof. Dr. Eva Groß

Professor of Criminology and Sociology at the Hochschule der Akademie der Polizei Hamburg. Her research focuses on group-related misanthropy, bias crime (hate crime), victimization/dark field, (online) radicalization, police, perceptions of crime, economization of the social sphere, and institutional anomie.

Prof. Dr. Ulrike Zähringer

Professor of Criminology and Criminal Law at the Hochschule der Akademie der Polizei Hamburg. Her research focuses on the emergence of prejudice, (serious) violent crime, and violence against children.

Dr. Anabel Taefi

Sociologist and research assistant at the Hochschule der Akademie der Polizei Hamburg. Her research interests include developmental criminology, (serious) juvenile crime, violent crime, and the emergence of prejudice.

Immersive technologies, such as virtual reality-based training, offer new opportunities for experience-based learning. Learners can immerse themselves in virtual or fictional worlds, making the experience feel real and allowing them to fully participate in it. These technologies also have great potential for basic and advanced police training in various subject areas, particularly in addressing bias crime, which is the focus here.The quality of police interactions with minority communities can greatly impact the level of trust these communities have in both the police and the state. Trust in institutions is an important measure of the quality of a democratic society, as it is intertwined with diversity and participation. This article demonstrates the potential benefits of immersive technologies in helping the police handle victims of bias-motivated crimes, which are often targeted at members of minority communities. Improving the professionalism of the police in this manner is a crucial step in building trust within minority communities and strengthening democratic resilience. The article then moves on to discuss a pilot project carried out at the Hochschule der Akademie der Polizei Hamburg, using virtual reality technology, and the initial evaluation results.

1 Bias crime and how the police handle them in Germany1This section builds on an earlier publication by the first author (Groß & Häfele, 2021) and contains text fragments that have already been published there.

Bias-based acts2From a criminological perspective, the term bias crime is more appropriate than hate crime, especially as the acts are an expression of group-related devaluation and discrimination (group-focused misanthropy) or negative prejudices against social groups that are linked to social structures of power and oppression, see also Fuchs, 2021, p. 270. and hate crimes are major issues when it comes to promoting diversity and inclusivity in many European countries. These acts specifically target individuals based on their social group membership and are based on protected characteristics, such as skin color, religious beliefs, or sexual orientation, under constitutional law (Groß & Häfele, 2021). The concept of bias crime (BC) is closely linked to the concept of group-focused enmity (Gruppenbezogene Menschenfeindlichkeit, GMF) (Heitmeyer, 2002), both of which revolve around the prejudiced belief in the inequality of different population groups (ideology of inequality) (Heitmeyer, 2002; Zick, Küpper & Heitmeyer, 2009; Zick, Wolf, Küpper, Davidov, Schmidt & Heitmeyer, 2008). This inequality can manifest in discriminatory attacks and hostile acts, such as racism, anti-Semitism, or transphobia. Therefore, the concept of bias crime theoretically covers the territory where prejudiced attitudes turn into concrete actions (Zick & Küpper, 2021). Although GMF and bias crime share a similar foundation, they are not identical. GMF focuses on attitudes, while bias crime deals with actions. In her study, Krieg (2022) was able to empirically prove the theoretical connection between GMF attitudes and the commission of discriminatory behavior, with a representative sample of students (N= 2824). What makes bias-motivated crime especially concerning is that, according to the logic of GMF, victims are not just targeted as individuals but also because of their group membership, either actual or perceived. These crimes not only harm the direct victim but also send a threatening message to the entire group to which the victim belongs (Groß & Häfele, 2021; Williams, 2021), making them damaging on a wider scale and threatening to democracy.

Since 2001, the police have officially recorded these crimes as “hate crimes” (Lang, 2014, p. 54). This includes crimes directed against a person or group of people due to their political stance, attitude and/or commitment, nationality, ethnicity, skin color, religious affiliation, ideology,or social status, physical and/or mental disability and/or impairment, gender/sexual identity, sexual orientation,or physical appearance (BKA, 2023). These acts can be directly committed against a person or group of persons, an institution, or an object/thing associated with one of the aforementioned social groups (actual or perceived affiliation), or against any target in connection with the perpetrator’s biases (BKA, 2023b). In Germany, as well as other European countries, there was a significant increase in officially reported hate crimes between 2014 and 2018 (Riaz et al., 2021). For the year 2022, 11,520 offenses were recorded in Germany, representing a 10% increase from the previous year (2021) (BMI & BKA, 2023, p.1 0). The few available studies on the unreported cases of bias crime in Germany indicate a very high number of unreported cases, ranging from 50% to 90% (e.g. Church & Coester, 2021; Fröhlich, 20213https://stadt.muenchen.de/dam/jcr:c19e83da-eca8-48b0-920e-e6e37791d4e7/Kurzfassung_DRUCK_final.pdf; Groß, Dreißigacker & Riesner 2019).

Just like the GMF concept, the BC concept and its reporting in Germany is continuously evolving to reflect social debates and developments. Since 2017, the new version of the police recording system includes “gender/sexual identity, sexual orientation” instead of the restrictive “sexual orientation” category, explicitly including trans* individuals in the police counts. In addition, the category of “race” was removed from the police recording system, and “physical and/or mental impairment” was added in 2017 (Groß & Häfele, 2021). Since 2017, law enforcement authorities have also been required to consider the perspective of the victim, among other aspects, when assessing the circumstances of the crime (Kleffner, 2018, p. 35).

Although the German police counting system is theoretically well-positioned, there are indications of quality gaps in the recording and perception of bias-motivated crime in police practice (e.g. Kleffner, 2018: 36; Habermann & Singelnstein, 2018; Groß & Häfele, 2021). There are significant differences in the statistics between those recorded by the police and those reported by independent counseling centers, suggesting an underestimation of bias crime based on police counts (e.g. Lang, 2015). For instance, specialized counseling centers registered approximately one third more acts of right-wing violence in 2017 than law enforcement agencies and offices for the protection of the constitution. When considering homicides linked to right-wing and racist violence as subcategories of the BC, the discrepancy between civil society and security authority counts is particularly significant, as noted in a comprehensive study of right-wing political homicides in Berlin from 1990 to 2008 (Feldmann et al., 2018). There could be various reasons for this high discrepancy. Errors in the initial recording by the police can lead to distortions. In addition, although some cases are reported to victim support services, they are not reported to the police. In a recent study4Groß, E., Häfele, J. & Peter S. (i.E.). Kernbefundebericht zum Projekt HateTown., it was found that the most common reasons for not reporting bias-motivated crime were fear that it wouldn’t make a difference, that the police wouldn’t be able to solve the case, and concern about not being taken seriously. These frequently cited reasons suggest a lack of trust in the police by those affected. Empirical evidence also supports this assumption, as victims of bias-motivated crime have been shown to have the least trust in the police compared to victims of non-bias-motivated crime and non-victims. This lack of trust is likely a key reason for the high estimated level of unreported crime in Europe.

Existing research in Germany confirms that many victims of bias crime feel that they are not taken seriously enough by the police or are treated inappropriately. This may be due to a lack of empathy, understanding, and proper training for police officers in dealing with bias crime. Unfortunately, this is not unique to Germany and is also seen in an international comparison. In 2018, the Greater Manchester Police (GMP) in England attempted to improve police officers’ sensitivity and professionalism towards those affected by implementing virtual reality training. This is where the VR headset-based training, aptly named “Affinity”, comes into play.

2 RESEARCH OBJECTIVE AND METHODS OF THE PILOT PROJECT: SENSITIZE POLICE OFFICERS TO THE EXPERIENCES OF VICTIMS OF BIAS CRIME

This virtual reality-based training, developed in cooperation with Mother Mountain Productions CIC (MMP) and Greater Manchester Police (GMP), allows officers to experience bias crime in a virtual setting by putting them in the role of victims in an immersive5“Immersive” means “to dive into” or “to immerse oneself in something” and refers to the effect that occurs in the consumer when they “dive into” the virtual or fictional world and it feels as if the experience is real and they are actually part of it. environment. Real-life stories of individuals who have faced anti-Semitism, trans-hostility, and attacks as people with disabilities are recreated using 3D technology and experienced through virtual goggles. The goal is to help officers understand how their initial reactions and language can affect victims and recognize stereotypes and justifications used by perpetrators in these types of crimes. The purpose of the training is to establish a connection and empathy with victims, in order to build trust in the police and increase reporting rates. Data collected so far6MMP & GMP, 2023. has shown that VR training has a significant and long-term effectiveness in changing attitudes and behavior among police officers, and also reinforces these changes among those who have already been sensitized.

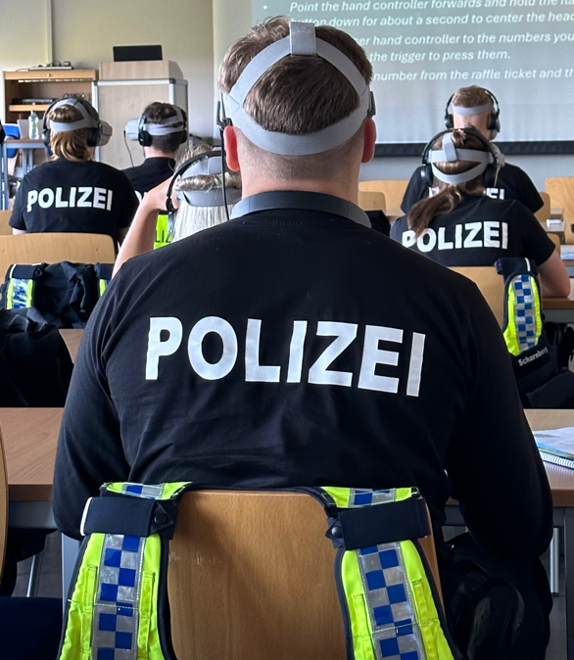

As part of the “Immersive Democracy Project”7The project immersive democracy is part of the European Metaverse Research Network with members in the Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Italy, Sweden and France. The aim is to conduct research that demonstrates both the liberalizing and highly beneficial opportunities of the metaverse idea as well as the potential risks and challenges associated with it. Further information on the project can be found at https://www.metaverse-forschung.de/en/about-the-project/ [17.10.2023], the European Metaverse Research Network is presented at https://www.metaverse-research-network.info [17.10.2023]., a quasi-experimental VR-based affinity training was conducted on August 21 and 22, 2023 at the Hochschule der Akademie der Polizei Hamburg in the Department of Sociology for future police officers.8This was followed by a one-day expert workshop with representatives from the police, academia, victim protection organizations, police students and teachers. The VR experience included original scenarios developed in collaboration with the GMP. The students were shown three English-language films where they experienced discrimination as victims of different marginalized groups, such as anti-Semitism, transphobia, and assault on a visually impaired person. The participants also experienced being questioned by the police after the incident from the perspective of the victim. The films were accompanied by re-enacted interviews with the actual victims describing their experiences during the assault and with the police.

The response patterns of the participating police students were measured through scenario-based questions designed to assess empathy before and after using the VR goggles as part of the Affinity project.9Specifically, the “Toronto Empathy Questionnaire (TEQ)”, a measurement method developed by Spreng et al. (2009), was used in the scenario-related development of the question formulation. It is a one-dimensional, concise and valid instrument for assessing empathy. As empathy itself counts as a comparatively stable characteristic, related behavioral and scenario-related questions were formulated that are suitable for a before-and-after measurement. The results of the quasi-experimental10In addition to the lack of randomization of the experimental group, no parallel control group could be investigated; the experimental element in the setting is therefore exclusively the treatment and the before-after measurement of the dependent variables. study on the changes in the participants’ attitudes towards victims of bias-motivated crimes are presented in the following section.

3 RESULTS

25 third-semester students from the police protection program, who were not randomly selected, took part in the pilot project. Out of them, 21 students completed the closed questionnaire before and after the VR application. The quantitative analysis is based on these 21 cases, and is not representative of the entire population of police students at the Hochschule der Akademie der Polizei Hamburg. Also, no control group was included in the study, and the lack of randomization only allows for a weak quasi-experimental design. Despite these methodological limitations, the comparison of the response patterns in the dependent variables before and after the VR application provides initial insights into the changes in the attitudes of the police students towards victims of bias-motivated crimes and the prevalence of such crimes.

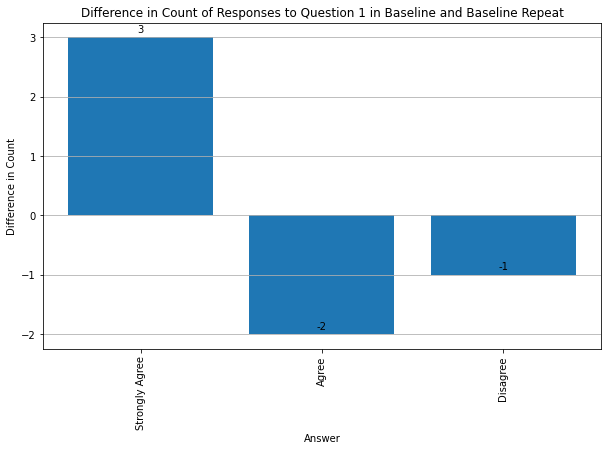

Figure 1 shows the difference in the response patterns of the 21 students before and after the application to the statement: “Hate crime should be a priority in police work.”

Figure 1: The difference in response patterns of the 21 students before and after the VR application to the statement: “Hate crime should be a priority in police work.”

Among the 21 cases, a strong agreement on the importance of prioritizing hate crimes in police work was clearly seen, with three cases showing an increase in agreement, while the other two categories showing a decrease. This suggests that the students became more attuned to the issue of hate crimes after the VR application.

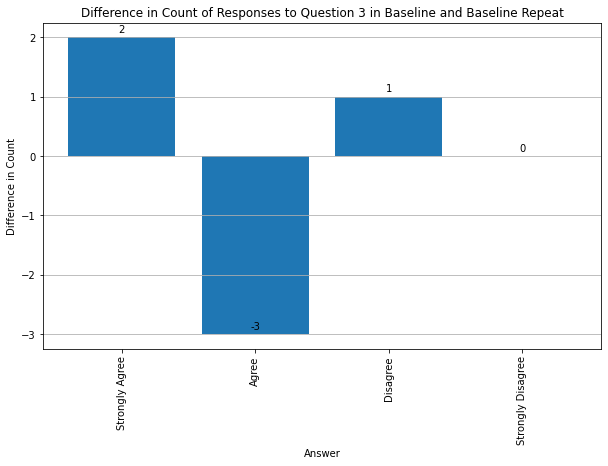

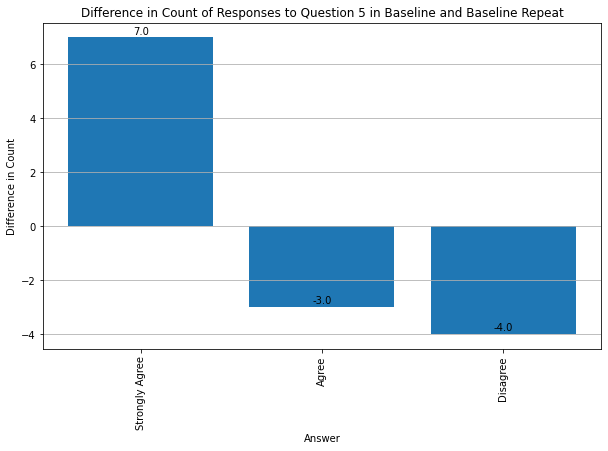

The statement, “Victims of hate crime should be more resilient and able to deal with the situation without reporting it to the police,” lost overall agreement among students after the VR application. However, the rejection of this statement increased (see Figure 2), indicating a higher sensitivity towards victims of bias-motivated crime.

Figure 2: Difference in the response pattern of 21 students before and after the VR application to the following statement: “Victims of hate crime should be more resilient and able to deal with the situation without reporting it to the police.”

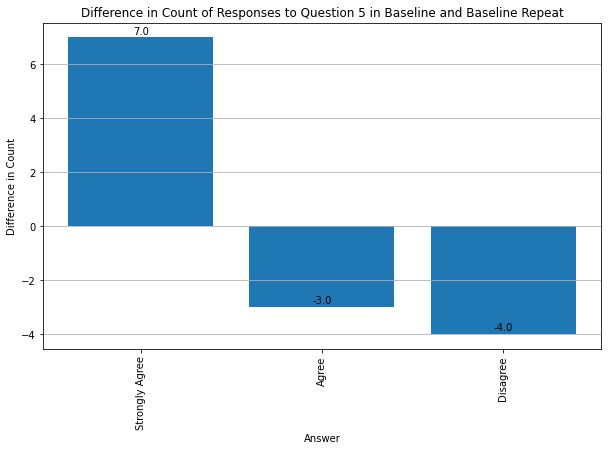

The statement following the VR application gained approval: “I believe that my way of interacting with a victim of a bias crime can influence that person’s ability to deal with what has happened.” (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Difference in the response pattern of 21 students before and after the VR application to the following statement: “I believe that my way of interacting with a victim of a bias-motivated crime can influence that person’s ability to deal with what has happened.”

As intended, this result indicates an increased sensitivity towards one’s own behavior as a police officer as a result of the VR application, and therefore, an increased reflection on one’s own behavior in the investigated situations. It can be assumed that the VR application leads to an increased sense of self-efficacy as a police officer when dealing with the sensitivities of victims of bias-motivated crime.

The change in the response behavior of the 21 students to the following statement points in a very similar direction: “The way I deal with a victim has the potential to improve the victim’s experience.” (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Difference in the response pattern of 21 students before and after the VR application to the following statement: “The way I deal with a victim has the potential to improve the victim’s experience.”

Overall, the collected quantitative data indicate an effect of the VR application in the intended direction for the Hamburg students, similar to what MMP and GMP found in their study of police officers from Manchester after 3 years (MMP & GMP, 2023).

In a qualitative design, the students were asked to reflect on their experience with the Affinity application and to share their thoughts and feelings. Many participants had a positive experience, as shown in the following examples:

- “It felt like I was there myself.”

- “I was directly engaged.”

- “I paid more attention compared to a movie, where I usually look away and get distracted.”

- “This made it easier to understand how people feel.”

- “This method is a good way to gather people’s points of view, which is important when they come into contact with the police. I immediately felt a tension that I’m sure those affected also feel, as they know it could happen again.

4 SUMMARY AND OUTLOOK

Hate crimes and bias-based crimes do not only affect individual victims, but also have a broader impact on corresponding social subgroups and the quality of democracy as a whole. Studies show that victims of hate crimes often do not report them to the police due to low trust. It must be in the interest of the police to undergo appropriate training and education to ensure that vulnerable victims, such as those affected by hate crimes, feel comfortable turning to the police for support. This could also help address the issue of unreported cases in this area.

To address this, the virtual reality-based training program “Affinity” was developed by MMP in collaboration with Greater Manchester Police. This training allows police officers, including trainees, to experience real-life stories of bias crime in an immersive environment. They can take on the perspective of the victims and witness the effects of verbal and non-verbal communication through the reactions of the interviewing officers. Additionally, they learn about stereotypical justifications associated with these acts, which helps them better identify and classify them. The training also aims to improve empathy among police officers. Initial data from England shows that this training has a high and lasting effectiveness on changes in attitude and behavior among police officers and reinforces the sensitivity of those already aware of the issues associated with bias crime.

Similarly, results from a pilot project at the Hochschule der Akademie der Polizei Hamburg with 25 police students also show the effectiveness of this training. The students strongly agreed that hate crime is a priority for police work, and their perceived resilience decreased while their awareness of their responsibility as police officers in dealing with hate crime increased. After the VR experience, they were also more likely to believe that their interactions with victims of bias crime can influence how they handle the crime and how they perceive and evaluate it in general. Thus, overall, a positive effect was also evident among police students in Hamburg – although the group of individuals tested was very small due to the pilot nature of the project, and thus the results cannot be generalized.

It should be noted that a simulated VR experience cannot truly replicate the perspective of those affected by bias crime and racism. However, other methods used in police training, such as role-playing or training with colleagues, have similar limitations, if not worse. The disconnection from the environment that occurs in the VR experience, due to the combination of 3D glasses and headphones, results in participants experiencing the simulation more intensely compared to other training courses. This was reflected in the comments of the students immediately after the VR experience.

Overall, this suggests that VR training in immersive environments holds promise in sensitizing police officers to dealing with victims of hate crime. The increased sensitivity of police officers may also lead to greater trust in the police and a higher likelihood of crime reporting by victims. In Germany, where different training concepts are used for prospective police officers compared to England, further research is necessary to assess the effectiveness of VR-based training with larger groups, using control group designs and longitudinal approaches. Additionally, scenarios designed specifically for Germany, including language, clothing, and environment, should be developed to make the experience as realistic as possible.

BKA (2023, 9. Mai). Politisch motivierte Kriminalität 2022 – Vorstellung der Fallzahlen in gemeinsamer Pressekonferenz. Bundeskriminalamt. https://www.bka.de/SharedDocs/Kurzmeldungen/DE/Kurzmeldungen/230509_PMK_PK.html (Zugegriffen: 08.08.2023).

BKA (2023b). Politisch motivierte Kriminalität (PMK) -rechts- Phänomen – Definition, Beschreibung, Deliktsbereiche. Bundeskriminalamt. https://www.bka.de/DE/UnsereAufgaben/Deliktsbereiche/PMK/PMKrechts/PMKrechts_node.html (Zugegriffen: 08.08.2023).

Church, D., & Coester, M. (2021). Opfer von Vorurteilskriminalität. Thematische Auswertung des Deutschen Viktimisierungssurvey 2017. Forschungsbericht. Kriminalistisches Institut, Kriminalistisch-kriminologischen Forschung, BKA.

Feldmann, D., Kohlstruck, M., Laube, M., Schultz, G., & Tausendteufel, H. (2018). Klassifikation politisch rechter Tötungsdelikte – Berlin 1990 bis 2008. Universitätsverlag der TU Berlin.

Fröhlich, W. (2021). Hasskriminalität in München. Vorurteilskriminalität und ihre individuellen und kollektiven Folgen. Kurzfassung der Studie des Sozialwissenschaftlichen Instituts München. https://stadt.muenchen.de/dam/jcr:c19e83da-eca8-48b0-920e-e6e37791d4e7/Kurzfassung_DRUCK_final.pdf (Zugegriffen: 25.10.2023).

Fuchs, W. (2021). Vorurteilskriminalität – Konzept, Auswirkungen auf Opfer, Rechtsgrundlagen und verbesserte statistische Erfassung. Journal für Strafrecht, 8(3), 279-294. https://doi.org/10.33196/jst202103027901

Groß, E., & Häfele. J. (2021). Vorurteilskriminalität. Konzept, Befunde und Probleme der polizeilichen Erfassung. Forum Politische Bildung und Polizei, 1/2021, 20-30.

Groß, E., Dreißigacker, A., & Riesner, L. (2019). Viktimisierung durch Hasskriminalität. Eine erste repräsentative Erfassung des Dunkelfeldes in Niedersachsen und in Schleswig-Holstein. Wissen schafft Demokratie, 4, 140-159. https://doi.org/10.19222/201804/13

Habermann, J., & Singelnstein, T. (2018). Praxis und Probleme bei der Erfassung politisch rechtsmotivierter Kriminalität durch die Polizei. Wissen schafft Demokratie, 4, 20-31. https://doi.org/10.19222/201804/02

Heitmeyer, W. (2002). Gruppenbezogene Menschenfeindlichkeit. Die theoretische Konzeption und erste empirische Ergebnisse. In Heitmeyer, W. (Hrsg.), Edition Suhrkamp: Vol. 2290. Deutsche Zustände. Folge 1 (S. 301). Suhrkamp Verlag.

Kleffner, H. (2018). Die Reform der PMK-Definition und die anhaltenden Erfassungslücken zum Ausmaß rechter Gewalt. Wissen schafft Demokratie, 4, 30-37. https://doi.org/10.19222/201804/03

Krieg, Y. (2022). The Role of the Social Environment in the Relationship Between Group -Focused Enmity Towards Social Minorities and Politically Motivated Crime. Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie 74, 65-94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11577-022-00818-7

Lang, K. (2014). Vorurteilskriminalität. Eine Untersuchung vorurteilsmotivierter Taten im Strafrecht und deren Verfolgung durch die Polizei, Staatsanwaltschaft und Gerichte. Nomos-Verlag.

MMP (Mother Mountain Productions CIV) & GMP (Greater Manchester Police) (2023). Affinity. VR Hate Crime Training Program 2020 – 2023 [Impact Review Präsentation]. Workshop in Hamburg 2023.

Riaz, S., Bischof, D., & Wagner, M. (2021). Out-group Threat and Xenophobic Hate Crimes: Evidence of Local Intergroup Conflict Dynamics between Immigrants and Natives. OSF Preprints. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/2qusg

Spreng, R., McKinnon, M., Mar, R., & Levine, B. (2009). The Toronto Empathy Questionnaire: scale development and initial validation of a factor-analytic solution to multiple empathy measures. Journal of Personality Assessment. 91(1), 62 -71. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223890802484381

Williams, M. (2021). The Science of Hate: How prejudice becomes hate and what we can do to stop it. Faber & Faber.

Zick, A., & Küpper, B. (2021). Die geforderte Mitte. Rechtsextreme und demokratiegefährdende Einstellungen in Deutschland 2020/2. Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung von Franziska Schröter. Dietz.

Zick, A., Küpper, B., & Heitmeyer, W. (2009). Prejudices and group-focused enmity – a socio-functional perspective. In A. Pelinka, A., K. Bischof, K., & K. Stögner, K. (Hrsg.), Handbook of Prejudice (S. 273-303). Cambria Press.

Zick, A., Wolf, C., Küpper, B., Davidov, E., Schmidt, P., & Heitmeyer, W. (2008). The Syndrome of Group -Focused Enmity: The Interrelation of Prejudices Tested with Multiple Cross-Sectional and Panel Data. Journal of Social Issues, 64(2), 363-383. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2008.00566.x

[1] This section builds on an earlier publication by the first author (Groß & Häfele, 2021) and contains text fragments that have already been published there.

[2] From a criminological perspective, the term bias crime is more appropriate than hate crime, especially as the acts are an expression of group-related devaluation and discrimination (group-focused misanthropy) or negative prejudices against social groups that are linked to social structures of power and oppression, see also Fuchs, 2021, p. 270.

[3] https://stadt.muenchen.de/dam/jcr:c19e83da-eca8-48b0-920e-e6e37791d4e7/Kurzfassung_DRUCK_final.pdf

[4] Groß, E., Häfele, J. & Peter S. (i.E.). Kernbefundebericht zum Projekt HateTown.

“Immersive” means “to dive into” or “to immerse oneself in something” and refers to the effect that occurs in the consumer when they “dive into” the virtual or fictional world and it feels as if the experience is real and they are actually part of it.

[6] MMP & GMP, 2023.

[7] The Project Immersive Democracy is part of the European Metaverse Research Network with members in the Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Italy, Sweden and France. The aim is to conduct research that demonstrates both the liberalizing and highly beneficial opportunities of the metaverse idea as well as the potential risks and challenges associated with it. Further information on the project can be found at https://www.metaverse-forschung.de/en/about-the-project/ [17.10.2023], the European Metaverse Research Network is presented at https://www.metaverse-research-network.info [17.10.2023].

[8] This was followed by a one-day expert workshop with representatives from the police, academia, victim protection organizations, police students and teachers.

[9] Specifically, the “Toronto Empathy Questionnaire (TEQ)”, a measurement method developed by Spreng et al. (2009), was used in the scenario-related development of the question formulation. It is a one-dimensional, concise and valid instrument for assessing empathy. As empathy itself counts as a comparatively stable characteristic, related behavioral and scenario-related questions were formulated that are suitable for a before-and-after measurement.

[10] In addition to the lack of randomization of the experimental group, no parallel control group could be investigated; the experimental element in the setting is therefore exclusively the treatment and the before-after measurement of the dependent variables.